Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR — 5 November 2018

The clocks went back, the days grew cold, the nights came down, and the money ran out… The legal system faces an autumn of despair and a winter of discontent. But there’s some good news, too, in our latest roundup.

Budget

Naught for your comfort

In what was billed elsewhere as a ‘giveaway’ budget the Chancellor of the Exchequer offered scant support for justice. The question of legal aid fees for barristers and solicitors remains unresolved, but judges were awarded a two per cent increase (backdated to April) which the Ministry of Justice said was “in line with that of other public-sector workers”. It was certainly not in line with the rises of up to 32% recommended in the major review of judges’ pay by the Senior Salaries Review Body (SSRB) (“thumping £60,000 pay rises” for High Court judges, as the Daily Mail headline put it), but apparently the government will be responding to those proposals at a later date. (See Weekly Notes — 15 October 2018 for more on this.)

There was money for prisons, however: “an additional £52 million to tackle prison violence, improve the prisons and courts estate and boost the operational capacity of the Parole Board this year after the Chancellor provided further funds for the department in yesterday’s Budget.” This is apparently in addition to the £40m promised in the summer. The £52m is made up of £30m to be spent on prisons, plus £15m to spend this year on the maintenance and security of court buildings, and another £6.5m to be invested across the wider justice system, including a further £1.5m for the Parole Board to boost its operational capacity.

Overall, though, the amount of money available for justice is going down. “The Ministry’s Spending Review 2015 settlement set the department on a course to reduce spend by 11% between 2015/16 and 2019/20”, according to the MOJ.

This continues a long downward trend. According to Funding for Justice 2008 to 2018: Justice in the age of austerity, a report by Professor Martin Chalkley commissioned by the Bar Council for Justice Week, “Cuts to justice are clearly way out of step with what happened in other areas of public spending.” The report shows that:

“in the 10 years between 2008 and 2018:

- Government expenditure has grown by 13 per cent in real terms

- Meanwhile, ordinary funding for the Ministry of Justice has fallen by 27 per cent

- Criminal Prosecution Service (CPS) funding fell by 34 per cent with less spent ‘per prosecution’

- Funding for legal aid fell by 32 per cent”

Chair of the Bar, Andrew Walker QC, said:

“This research explains the context of the enormous disinvestment in justice over the last 10 years, and highlights just how badly justice has been treated in comparison with other areas of government expenditure. For a system that is fundamental to a healthy democracy, society and economy, this is scandalous. The state is failing in its fundamental duty to provide justice for its citizens.2

In her latest post on Transform Justice, citing that report and other material, Penelope Gibbs asks Why is the justice system so starved of resources?

Legal aid

Means test report

Research from the University of Loughborough, commissioned by the Law Society, has found that the legal aid means test is preventing families in poverty from accessing justice.

The report by Professor Donald Hirsch, entitled Priced Out Of Justice, shows that people on incomes already 10 per cent to 30 per cent below the minimum income standard are being excluded from legal aid, meaning that poverty hit families are being denied vital help to fight eviction, tackle severe housing disrepair and address other life-changing legal issues. Its central finding is that:

“the means testing of legal aid is set at a level that requires many people on low incomes to make contributions to legal costs that they could not afford while maintaining a socially acceptable standard of living. In particular:

- At the maximum level of disposable income at which legal aid is allowed, households have too little income to reach a minimum standard of living even before footing any legal bills. Typically, they have disposable incomes 10% to 30% too low to afford a minimum budget.

- Even those below the disposable income limit, while eligible for legal aid, are required to make a contribution to legal costs, unless their income is extremely low. Some households who can afford less than half of a minimum budget must still contribute to legal expenses. This includes households whose income would only be just enough to pay for food, heating, travel and housing costs, even before meeting other expenses such as clothing, household goods and personal care items.”

Based on the report findings, the Law Society is calling on government to restore the means test to its 2010 real-terms level, and to conduct a review to consider what further changes are required to address the problems exposed by the report.

Debate in the House

Further calls for review came in a three-hour debate on the Future of Legal Aid in the House of Commons on 1 November, following a motion by Andy Slaughter MP, which is reported in Hansard. He began:

“We are in Justice Week, the aim of which is to show the significance of justice and the rule of law to every citizen in our society and to register the importance of an effective justice system beyond the usual audience of professions and practitioners. That aim is reflected in the many representations and briefings we have received in preparation for this debate. They have come not only, as one might expect, from the Law Society, the Law Centres Federation, LawWorks and the Equality and Human Rights Commission, but from Mencap, Mind, Oxfam, Amnesty International, Youth Access and the Refugee Council. The message is that legal aid is important to everyone, but particularly to the poorest and most vulnerable.”

Honorable mention

Emily Dugan, whose reporting for Buzzfeed News on issues around legal aid and access to justice has been absolutely outstanding, was justly given an honorable mention in the 2018 WJP Anthony Lewis Prize for Exceptional Rule of Law Journalism.

On 26 October 2018 the World Justice Project (WJP) announced as the winner a reporting team from Mexico’s Animal Político are the 2018 prize winners for their investigative reporting series, “To Murder in Mexico: Impunity Guaranteed.” In addition to the prize winners, six journalists were awarded Honorable Mention in recognition of their extraordinary reporting on rule of law issues: Diego Cupolo (based in Turkey); Christian Davies (based in Poland); Alice Driver (based in Mexico); Emily Dugan (of the United Kingdom); Emily Feng (of China); and Kirsten Han (of Singapore).

Crime

Obscene publication

The most notorious obscenity trial in the history of English law must be that of Penguin Books for its paperback edition of DH Lawrence’s novel, Lady Chatterley’ Lover. The novel was first published privately in 1928 but it was the prospect of its wide distribution in a cheap paperback edition in 1960 that aroused the concern of the prosecutorial authorities. The trial was famous for a number of reasons, not least the anachronistic invitation of prosecuting counsel Mervyn Griffith-Jones that the jurors should, when reading the book, ask themselves:

“would you approve of your young sons, young daughters — because girls can read as well as boys — reading this book? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?”

That was not really the question they had to settle. By section 1 of the recently enacted Obscene Publications Act 1959, an article was deemed obscene if its effect would “tend to deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read, see or hear the matter contained or embodied in it”. But by section 4, it was a defence to show that “publication of the article in question is justified as being for the public good on the ground that it is in the interests of science, literature, art or learning, or of other objects of general concern”. To establish such a defence, “the opinion of experts as to the literary, artistic, scientific or other merits of an article may be admitted in any proceedings under this Act”.

Penguin was represented by Jeremy Hutchinson, led by Gerald Gardiner QC, who duly called as witnesses a number of leading figures from the arts world in order to establish, somewhat absurdly, that a book which tended to deprave and corrupt anyone looking at it was nevertheless justified as being for the public good. The ensuing forensic farce ended in an acquittal, generating massive publicity and therefore sales for the book (which might otherwise have enjoyed only modest circulation, being by no means the best work of its author).

The trial has generally been considered a watershed moment in social history, confirming the sexual revolution of the 1960s. As the poet Philip Larkin observed,

Sexual Intercourse began

in Nineteen Sixty-Three

between the end of the Chatterley ban

and the Beatles’ first LP.

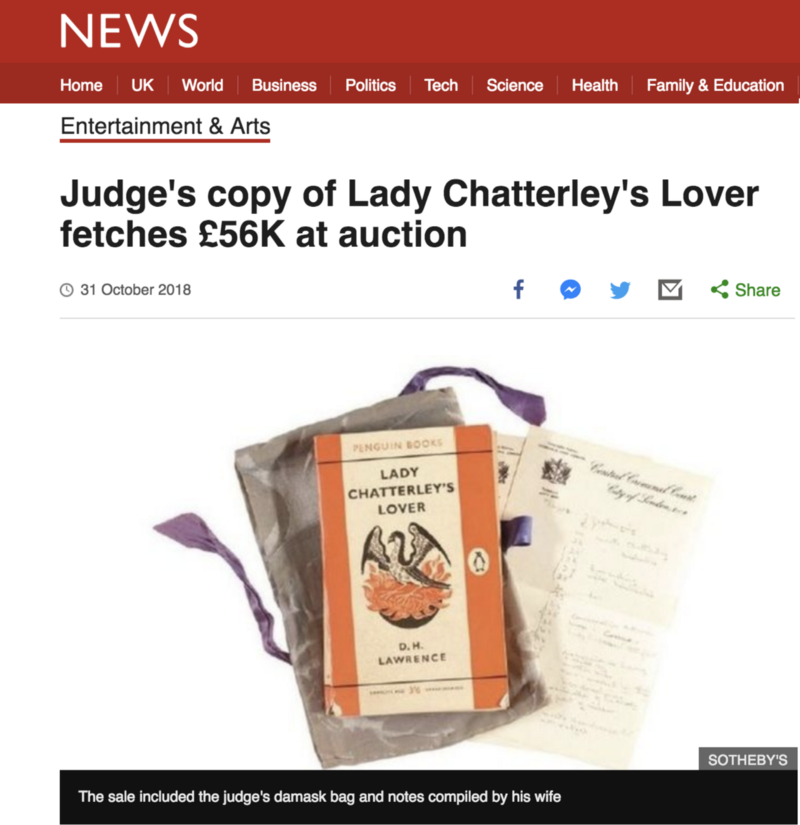

The reason all this has become topical again is that the copy of the book used by the trial judge, Sir Laurence Byrne, recently came up for auction and was sold for £56,250 — more than five times the pre-sale estimate. Byrne J is said to have carried the novel in and out of court every day concealed in a blue-grey damask bag hand-stitched by his wife Dorothy. According to a BBC report:

“Before the trial, Lady Dorothy Byrne read the book and marked up the sexually explicit passages for her husband. She compiled a list of significant passages on the headed stationery of the Central Criminal Court, noting the page number, and adding her own comments, such as ‘love making’, ‘coarse’, and so on.”

Although the verdict was a setback for the prosecuting authorities, it did not preclude further prosecutions under the 1959 Act, which is still in force. The tension between sections 1 and 4 of the Act was the subject of the later case of R v Calder & Boyars Ltd [1969] 1 QB 151, which concerned Hubert Selby Jnr’s novel Last Exit to Brooklyn. The defence on that occasion was that, far from tending to deprave and corrupt, “the only effect the book would produce in any but a minute lunatic fringe of readers would be horror, revulsion and pity”. (Thank you John Mortimer QC.) The Court of Appeal assessed the directions given by the trial judge and ruled on the approach to be adopted in such cases, observing that “The jury must set the standards of what is acceptable, of what is for the public good in the age in which we live”. That was, in effect, what the jury had done (much to Griffith-Jones’s disgust) in the Chatterley case.

Legal information

Harvard free case law project

The Library Innovation Lab at the Harvard Law School Library announced the launch of its Caselaw Access Project (CAP) API and bulk data service, which puts the full corpus of published U.S. case law online for anyone to access for free.

Between 2013 and 2018, with the partnership and support of Ravel Law, Inc., the Library digitised over 40 million pages of U.S. court decisions, transforming them into a dataset covering almost 6.5 million individual cases. The CAP API and bulk data service puts this important dataset within easy reach of researchers, members of the legal community and the general public.

To learn more about the project, the data and how to use the API and bulk data service, please visit case.law.

EU law site guide

The Middle Temple Law blog has a useful post explaining the new design and functionality of the European Union’s official online sources of legal materials, EUR-Lex and Curia.

“The update of EUR-Lex has mostly affected the design and navigation of the database, with the major changes being visible immediately. You will see a new home page which is dominated by four categories — EU law; EU case law; National law and case law; Information. They are further divided into subcategories.

On Curia, which is the official website for the courts of the European Union and therefore contains the e-ECR (electronic versions of the European Court Reports), the search functionality is exactly the same, but the site has undergone some cosmetic changes, as well as added a few new features to the front page.”

There are further explanations and user tips together with screengrab illustrations to help users navigate and search both sites.

ICLR.3 will be expanding the external links to case law in coming months, including to the Curia site which hosts original ECJ judgments. (Currently these are indexed with citations, so linking out will be the next stage.) You can also read about the court itself here: A visit to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg

Dates and deadlines

Drawing the Law

Sussex Law School, Wednesday 7 November, 3–5pm

Isobel Williams (who tweets as @otium_catulle) is the artist and blogger who occasionally writes about what she draws in the UK Supreme Court, with the court’s permission. She will be asking, how does it look from the public seats and how does the non-lawyer interpret the coded theatre? How does the legal process cauterise emotion? How does drawing in a court fit in with other parts of Isobel’s practice such as drawing Japanese rope bondage in performance?

Click here for details.

Russia Law Week

Law Society and Lincoln’s Inn, London, 12–14 November 2018

Russian Law Week will bring together Russian and English and Welsh lawyers to share insights, strengthen legal relations and encourage excellence amongst the professions. It is a fantastic opportunity for English and Welsh legal practitioners to meet with Russian counterparts to discuss current trends in legal services in Russia and England and Wales.

Organised by the Law Society and Bar Council, in partnership with the Russian Federal Chamber of Lawyers, the Moscow Chamber of Advocates, the St Petersburg Chamber of Advocates, the Anglo-Russian Law Association, and the British Russian Law Association. Click here for registration.

ALC conference

Bristol Marriott City Centre, 22 to 24 November 2018

The Association of Lawyers for Children’s 29th annual conference takes place in Bristol, with Sir Andrew McFarlane, President of the Family Division, as keynote speaker.

To make a booking please visit the ALC website: www.alc.org.uk and click on ‘Events and Training’. Click here for more details.

Law (and injustice) from around the world

Ethiopia: first woman chief justice

For the first time in its history, Ethiopia has a woman Chief Justice. African.Lii reports that Meaza Ashenafi, who was nominated by Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, was sworn in as the head of the Federal Supreme Court on 1 November 2018.

Ashenafi is a prominent women’s rights activist and former judge of the High Court of Ethiopia, and was the founder and executive director of the Ethiopian Women Lawyers Association (EWLA). She was the lawyer in a case about kidnapping child brides that became the subject of the film Difret, produced by Angelina Jolie and others, which won the World Cinematic Dramatic Audience Award at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival. Her appointment has been characterised as part of Ethiopia’s “move to empower women”.

Pakistan: blasphemy conviction quashed

The Supreme Court of Pakistan has reversed the conviction of a Christian woman, Asia Bibi, for blasphemy, despite popular opposition in the mainly Muslim country.

Bibi was initially convicted and given a death sentence for blasphemy in 2010 following an argument with neighbours in which she was said to have insulted the prophet Mohammed. She has been in prison ever since, pending her appeal to the Supreme Court. Her cause was championed by international human rights groups and by a provincial governor in Pakistan — who was then assassinated, apparently because of his support for reforming the blasphemy law. (His killer was convicted and received a death sentence.)

Following her acquittal, Bibi’s release was delayed over fears for her safety. Her lawyer has fled the country, and her husband has petitioned the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom for asylum on the grounds of the risk posed to her life if she is required to stay in Pakistan. Meanwhile, protesters took to the streets demanding that the Supreme Court reverse its ruling and that the three justices on the panel, including Chief Justice Mian Saqib Nisar, be dismissed.

The UK Human Rights blog commented:

“The case of Asia Bibi raises not only profound questions regarding the protection of human rights in the country, but also more substantial concerns about the rule of law, constitutional balance and ability of the government and courts to impose their will in a nuclear armed state at the forefront of some of the world’s most acute geo-political challenges.”

UPDATE: Thanks to the industry of Matthew Scott, as BarristerBlogger, we have been able to index the PDF judgment of the Pakistan Supreme Court and provide a link to his web transcription: Asia Bibi v The State (Unreported) Criminal Appeal NO.39-L OF 2015, 31 October 2018.

Tweet of the Week

Katie Gollop considers a legal cocktail.

From seminal case to hipster cocktail.

Feel sure Lord Atkin would approve… pic.twitter.com/MarjOZaUwc— K (@katiegollop) November 1, 2018

No prizes for guessing that the case is Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562, HL(Sc)

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading. Watch this space for updates.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.

Featured image: picture by Sarah P in tribute to the Bristol to Plymouth line